GRU/AAF Casepulse round

A standard bullet propelled by a small pulse charge

None

The bullet is made from layers of lead, steal, and copper. The propellant is Pulsefuel.

Unknown

Unknown

Slightly expensive

Uncommon

The casepulse round is a special purpose cartridge that fires a very high-velocity projectile using a pulse propellant detonated by a standard primer.

The Casepulse began as an experimental foray into high energy solutions to the stagnation of conventional cartridges. With rapid advances in lightweight advanced armor for infantry and vehicular armor nearing impenetrability from handheld firearms, the AAF predicted that over the span of a few decades, most intermediate conventional weapons would become ineffective at penetrating body armor at ranges over 150 meters.

The design of the first Casepulse, the 10mm, was centered around the need to fire a round capable of penetrating an AAF main body plate at 1000m. The research team at the time considered this a tall order. The body armor, which many on the Casepulse program had been a part of designing, had been known to stop full-size anti-material bullets at ranges of 750m. The prototype Casepulse was based on a likewise prototype caseless round that, while larger than average, was still considered intermediate. Many researchers on the team expressed their doubts about the merit and effectiveness of such expensive ammunition, considering it a waste of a scarce resource. Nonetheless, their funding was generous and costs met, and they continued development, creating the first prototype rounds after 2 years of chemical analysis of the propellant. The test round was loaded in a donated SR-AR 10mm, stripped down to its barrel and chamber, pointed at an AAF chest rig 50m away in the indoor range of the Armament Development Center. The lead engineer, in an attempt to demonstrate the futility of the research, placed three inflated balloons along the projected flight path, one in front, in, and behind the chest plate. He predicted that the first balloon would be enough to stop the projectile because the energy released from the detonation would be enough to melt the bullet entirely.

After a number of wagers, the research team fired the first shot, which penetrated the front and back plates of the armor, 5 meters of concrete, and lodging inside of a structural steel beam in an office building across the street. High-speed footage taken of the bullet's flight estimated velocity of 5550 feet per second, almost twice as fast as any existing round in AAF inventory. Analysis of the fragmented bullet and its path of destruction detailed that the high energy pulse propellant after firing coated the bullet and barrel in a layer of dense combusted material, insulating it from the superheated gasses of the propellant and giving the bullet extreme penetrating characteristics. These materials were shaved off as it passed through the concrete, allowing the subsequent metal beam to put the bullet to a stop. Testing was subsequently moved outside to an isolated area used as an armored vehicle proving ground.

Further tests and alteration to the chemical makeup of the pulse propellant managed to increase the velocity another 200 feet per second out of an SR-AR 10mm, bringing the muzzle velocity up to 5750 fps. This outstanding velocity flattened served the flatten the ballistic trajectory throughout the intermediate-range and out to 1000m, although, due to the ballistic arc, the round tends to float high in ranges closer than 200m. Against light armor, the 10mm bullet has good penetration at an angle of incidence at or less than 20 degrees at 750m but quickly falls off in penetration chance at greater angles and ranges due to the lack of a proper penetrator head, impractical to mount on such a small bullet. The round performs well against infantry armor, however, and ultimately exceeded the team's 1000m goal by 300m.

When the Standard Rifle Program started the development of different calibre weapons, the Casepulse program followed suit, developing a round for the SR-SMG 5mm and the SR-SR 15mm weapons. The small size of the 5mm meant that, when propelled by a pulse charge, the bullet cut through the air at an extreme velocity of 6300 fps, thanks to a more favorable aerodynamic shape. However, drag and lack of inertia would start to slow the round quickly, leaving the effective range at an impressive 750m.

The 15mm Casepulse round was more problematic. There were serious concerns about the handling of such a large quantity of pulse ammunition, which was believed, at the time, to be more volatile than gunpowder. Many officers compared carrying a load of 15mm casepulse round to carrying a cordite charge from an old battleship, fearing that high explosives from enemy action could set off pulse charge, creating a far larger explosion. This fears were especially prevalent in regards to potential vehicular mountings of 15mm casepulse weapons, since the ammunition load would be far greater, and in an enclosed space where ignition sources could be found more easily. These fears prompted significant research and testing in areas relative to the round's safety.

While an independent, military funded commission was launched into the safety of pulse ammunition, development of the 15mm casepulse round continued, ultimately delivering a round capable of 4500 fps muzzle velocity out of an SR-SR 15mm, giving it

After several years of analysis, three primary observations were returned.

Firstly, pulse ammunition of all types were, indeed, more explosive than any other known compound. The commission pointed out that this was precisely the reason weapons were being developed for it: it produced a considerably stronger reaction per gram than any alternative.

Secondly, pulse ammunition will detonate uncontrolled due to external events. These events are incredibly specific, however, and present little to no risk in routine use. The only thing that was able to successfully detonate pulse ammunition was the introduction of a pulse reaction already in progress. That includes, but is not limited to, the combustion chamber or direct exhaust of a pulsefuel starship engine or direct contact with deflagrating pulse particles from firing pulse ammunition. For detonation to occur in the latter case, the rapid firing of fullpulse ammunition is necessary. Casepulse ammunition does not have enough escape gasses as they are trapped by and embedded into the physical bullet and barrel. In fullpulse, the deflagrating particulates are the bullet, which transfers through the air like sparks after exiting the barrel and may land on objects in front of the barrel. However, for the ammunition to cook off, the required number of landed particulates is inversely proportional to the ammunition's temperature. As a practical example, to detonated the test ammunition at high outdoor temperatures required a full two minutes of fully automatic fullpulse gunfire taking place right above it to detonate. As the ammunition detonated, the barrel was melting away.

This led to the third observation. That pulse ammunition did not present a unique safety concern when compared to traditional gunpowders. It was more stable than other compounds, although it did indeed have the ability to detonate, and if they did occur, such detonation were considerably powerful. However, high temperatures alone would not cause detonation. A pulse reaction was the only thing capable of causing an uncontrolled pulse reaction, as part of a function of the temperature of the ammunition in question. Therefore, the commisoin predicted that pulse ammunition would be safe to use in vehicle cannons and even naval vessels, especially those with the capability to flood magazines. The commission did concede that, without further research into large caliber fullpulse rounds, fullpulse shells, or mixed effect shells that had pulse effects, such a declaration would be premature and not founded by sound research.

Polymer, Pulsefuel

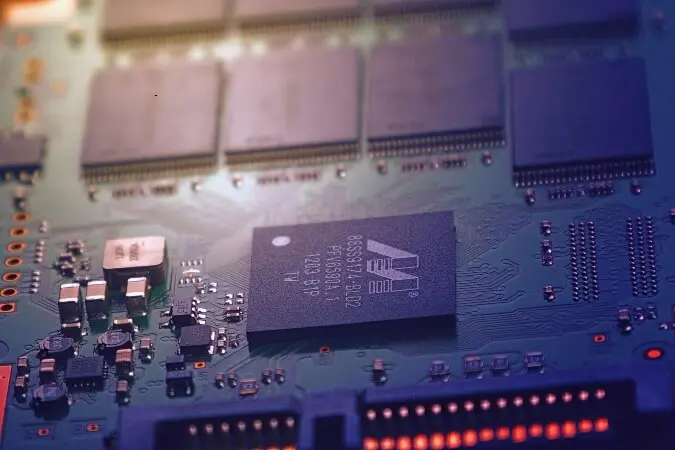

The Casepulse round is a straight walled, rimless centerfire catridge. A standard FMJ bullet is attached to a Pulse cartridge.

The most common casepulse size is the 10mm standard

The Casepulse Round weights in at 25 grams each.

The bullet is yellow and the charge is blue

None

This technology was created by GRUsturmovik on Notebook.ai.

See more from GRUsturmovikCreate your own universe